By Terikel Grayhair

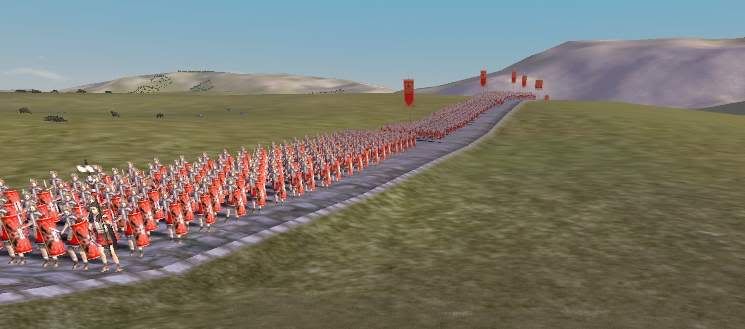

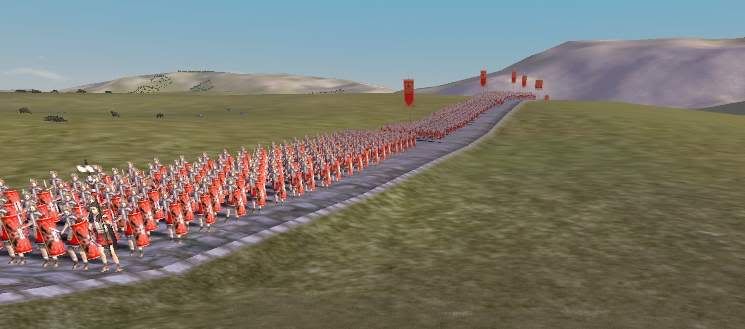

The Via Mala was a stone snake leaving the mighty Alps behind, slithering through rugged hills before reaching its head at Argentoratum. Along its cut-stone back writhed another snake, this one clad in armor and bearing the Pegasus standards of the Legio II Adiutrix. Behind that snake, others followed. The VIII Augusta, the XI Claudia, the XXI Rapax, and the XIII Gemina completed the army of Quintus Petillius Cerealis.

Legate Marcus Rutilius was pleased with the honor his men had earned in leading this mighty force, though he was less pleased with the reasoning behind it. As the generalis saw it, the II Adiutrix- being promoted from marines and therefore the least valuable legion he had- would serve well to hold the attention of any attacking foe so that he could maneuver his better, veteran legions to crush the impudent foe. Despite the insidious reason, Rutilius was grateful for the honor of having his legion lead the march into potentially hostile territory.

Argentoratum was just ahead when a messenger from the general came and ordered the halt. Rutilius dutifully obeyed, deploying his legion on good ground into a square with the accumulated baggage trains in the middle. The sun was setting, and it was always easier to build a camp when the trains were already inside the perimeter.

Quintus Cerealis himself came to the head of his column and nodded his shaggy head with approval at the deployment of the II Adiutrix.

"Your men did that well, Rutilius," he commented. "Almost as good as the VIII Augusta."

"Thank you, sir," the legate replied proudly. It was not often his men received praise from higher- not often at all. He made a mental note to pass the praise on to his men. "I still have no cavalry, sir, but I deployed a century from each cohort to patrol the area immediately around the legion."

"That will be necessary," Cerealis agreed. "Get used to this terrain, Rutilius. Your men will be staying here while the rest of us move on to Moguntiacum tomorrow. Your mission will be to rebuild and man the abandoned castella and restore the integrity of the border, from sixty miles south of here to thirty miles north. Put in a requisition for cavalry- you will need it."

The orders made Rutilius livid with frustration and rage. He had personally trained his men from wet-legged marines to dry-land soldiers, and they out-marched and out-performed every legion in the army. They had proven their worth, and deserved to participate in the upcoming battles as much as anyone.

But the generalis did have a point, deflating his anger somewhat. With the border castella destroyed or abandoned, the Upper Rhenus was open to invading hordes that could just as easily enter Italia through the Via Mala as he had so recently exited it. The castella were necessary, but by the gods, they did not have to be garrisoned with his II Adiutrix!

"Sir, I strongly disagree with that disposition," he spat out after a few seconds, having regained command of his turbulent emotions. "I do agree that the castella need to be garrisoned and rebuilt, but disagree that the II Adiutrix is the legion to do it. We are former marines, as you so commonly sneer, and know little about stone formations, though we can put up a proper wooden and earth camp every night."

"I have noticed," Cerealis grinned. "Silly of you to do that, with four other legions about."

"Protocol, sir," Rutilius rebutted. "Secondly, the VIII Augusta served in this area before Vitellius took it south to win the throne. They know all the clever places to infiltrate, while my men do not."

"You can learn," the commander retorted angrily.

"And how many will die because we missed a few? How many could sneak through a gap in ourlimes because we have no cavalry with which to patrol? My men are just learning the uses of terrain," Rutilius replied evenly. "How effective would these men be for the first, most vital years, of garrison in this area?”

Having adequately refuted his commander’s arguments for stationing the II Adriutrix here, he continued on with his reasoning of why they ought to remain in the main army. “”Third, I was sent to you as the personal legate of the consul Gaius Licinius Mucianus. I am required to remain with you, sir, where I can advise you against actions that could lose Rome this army- like you lost your IX Legion at Camulodunum nine years ago, or most of your cavalry turma against the walls of Rome this December past. That duty of mine has prejudiced you against me, and my men. The only true reason you chose my legion for garrison here was to be rid of me and my irritating presence. So I disagree with your disposition on this matter. It would be far better- tactically and strategically- to give this mission to the VIII Augusta, who lived here and have wives here. Sir."

Cerealis ran the arguments through his head backwards and forwards, and came to the same conclusion every time- as much as he hated to admit it, Rutilius was correct on all counts. He had been extremely prejudiced against the II Adiutrix because of their humble origins and their legate's status. He made a silent vow to himself that he would try to avoid that in the future.

"So be it, Marcus," he acknowledged, using the legate's given name for the first time. It was an admission of respect, which the younger man had earned several times over. "The VIII Augusta shall take over the rebuilding. Your men will continue along with us to Mogunticaum- but following the XXI Rapax. The area will be getting more dangerous, and although your men have improved greatly, it would be foolish of me to leave such a junior, untested legion in the lead."

Rutilius nodded, ambivalent at the decision. He felt a loss of honor at the legion's removal as the leading legion, yet the generalis made a good- and for once, unbiased- decision based on the nature of his forces. The II Adiutrix, not matter how hard they had trained and drilled during the march, was still an unblooded legion. Until it had drawn blood and shed some of its own, it would always be of an unknown quality.

"Aye, sir," he acknowledged, thumping a fist to his heart in salute.

The general called a council of his legates to pass the new orders, while Rutilius signalled to his Praefectus Castrorum to begin the nightly camp-building drill. It was going to be a long night as the army reorganized itself into combat formation and readied itself for the next phase.

********** *********** ************ **************

“They come.”

Julius Classicus shuddered at the words. Once the Treveri chieftain, he was now a full-fledged general of the Gallo-Batavian alliance- commanding his own Treveri warhost, some Lingone cavalry, and a rather large band of Frisians, Chauci, and Tencteri warriors together with Suevii and other Germanics from across the river. He had sixteen thousand men under his command, many trained under the Eagles as auxilia, yet the uttered words still shook him uneasily. The Eagles were coming. Again.

“How many, Inditrix, and where?” he asked in a voice stronger than his emotion.

“We saw five Eagles,” the Treveri captain replied. “South of the Crossroads Fort but coming this way. Mornix said that fifth Eagle warhost peeled off. Most likely it will remain there, rebuilding the fortifications we demolished following their abandonment.”

Classicus sighed. Four legions. That was not too bad. He could handle that. Maybe. “And where is Seval, our great ally, with that wonderful army of his?”

Inditrix shrugged. “He had gone west in the spring to confront his cousin. Word has it he took his cousin’s army from him in a bloodless battle, won over the Tungrians, then plundered their civitas in a crude gesture. Since then he has been trying to chase down his cousin, who escaped. It is proving very difficult.”

“He isstill at that!?” roared Classicus. “He chases a powerless fugitive for honor’s sake, while four legions of Romans descend upon him from the High Hills? Has he gone as mad as that party-hair he wears?”

Inditrix laughed. “He cut that silly crap off when he danced in the ruins of Vetera, as he had promised and the seeress Veleda had foreseen. But yes, he is still trying to pin down his royal kinsman.”

“Send a runner to him now, my friend,” Classicus ordered. “Tell him to cease that fruitless and useless hunting of his fugitive cousin and get his army over here where the main event will be taking place shortly. Oh, by the way,” he added with a sweet smile, “phrase it nicer than I did, please. We can’t go around angering our allied king. In the meantime I will let our Germanic apes continue the siege here at Moguntiacum while the rest of our Gallic forces to blunt the Roman forces a bit.”

Inditrix saluted and turned to go. He stopped suddenly and turned back to his commander. "Be careful blunting those Romans, lord. Make sure they do not blunt you instead."

Classicus nodded solemnly. "I misspoke. You be careful blunting the Romans, my brother. I intend to remain here with the Germani. You will skirmish, Inditrix, and skirmish only. You yourself said you saw no horsemen screening the two leading legions as they came out of the mountains. Leading legions are always the strongest. If they had none, neither does the rest of the army. They are footmen, the entire lot. So how do you expect those sandaled fools to catch fleet Gallic cavalry?"

Inditrix laughed at the thought of an armored Roman infantryman chasing a Gallic horseman and relaxed. Classicus was a good general, and correct. The fleet cavalry will give the Romani a bloody nose with very few Gallic lives lost in the process.

********** *********** ************ **************

A cadet raced his steed back along his legion, the XXI Rapax, towards the army command group following the II Adiutrix. He paused at the legion's headquarters long enough to spread the word, then sped on to report to Cerealis.

Salvius came up to Rutilius as the cadet galloped off.

"What was all that about?" he asked bluntly, as was his way.

Rutilius shrugged. "There is a band of Gallic horsemen approaching his legion. Evidently they were many, so he is seeking orders for his commander. At least he was nice enough to give us a heads-up about what will be coming down."

"Gallic horse, especially in numbers, is nothing to sneeze at," the old Prefect agreed. "After the Batavians, they have the best cavalry in the Empire."

"Issue the hasta, Publius," Rutilius ordered. "Gallic horse haven't faced hasta since Telamon. They are used to the pilum. Let us blood our legion in the best possible way- bloodlessly."

Salvius saw where Marcus was going and smiled. "Yes sir!"

********** *********** ************ **************

Inditrix was indeed true to his word. He skirted the deploying cohorts of the XXI Rapax, closing to lure the legionaries into casting their pila, then bolting from the area while the pila were in flight, rendering them useless. Then they would return in a charge, shatter a cohort's formation, slay a few exposed legionaries, then race off before supporting cohorts could render assistance.

Then he repeated the tactic again, and again, bleeding the Rapax from a hundred tiny cuts until it finally did the only thing that was sensible- forming up into a large square with its archers in the center. Seeing the legionaries hold their position, he knew this legion was going nowhere. Now it was time to harass the next legion and stop it, too.

********** *********** ************ **************

"Lucius Pallius," Rutilius asked his primus pilus. "What is the range of those naval bows of yours?"

Pallius, an old sea-eagle turned dry-foot legionary, looked over the approaching Gauls and smiled. "About another hundred paces, sir, is when I would give the order to let fly."

"As will I," Marcus Rutilius agreed. He let the Gauls get set, then had the trumpeter blast out the command for "Legion! Raise bows!" After a small delay in which the Gauls started moving, the loud, shrill single blast upon the horn unleashed a devastating hailstorm of thick naval arrows into the packed masses of Gallic cavalry readying their attack.

The cavalry, well within arrow range but far from the pila they expected, were caught totally unawares. The naval arrows fell among them like angry wasps, emptying saddles of men who thought themselves safe. A second and third volley landed before Inditrix awoke from his shocked reverie and ordered his men to charge.

"Here they come, as pissed as they made the Rapax," Rutilius commented. "Trumpeter- sound the lower bows. And now Brace Spears."

As the notes floated across the legion, bows were discarded and the hasta picked up. Centurions took over from there, ordering their men to brace the buttspikes in the ground and lean the hasta forward, just as the thundering Gauls realized what it was they faced. These were no pilum-armed swordsmen- these were bow-armed spearmen. The leading horsemen braked en masse, rearing their horses up and away from the deadly points, disrupting the entire charge as the charging horses behind piled up upon the rearing horses in the front.

The trumpet blew a simple, short command. Charge! And with that, the II Adiutrix left its defensive stance and charged into the stirring, confused mass of Gallic cavalry, stabbing with their hasta into horse chests, and drawing their gladii as spears stuck in the dying horses.

Inditrix died under the spears of the first wave of Romans crashing into his plunging horses. His cousin Mornix in the second, and then many, many more followed the Gallic chieftain into the mud. The rearward Gauls, finally realizing the danger, raced away to give the men of the fore ranks space into which to escape. The knot loosened, and the Gauls began streaming away from the deadly crush. Several hundred horsemen fled away from the place where thousands had charged.

Behind them, grinning centurions reformed their men and gathered up their bows, in case the Gauls were stupid enough to return for a second pounding.

********** *********** ************ **************

The surviving Treveri chieftains called the retreat when word came of the result of Inditrix's disastrous attack on the second legion. They trotted back to Moguntiacum with their tails between their legs like whipped curs.

Damn, Classicus cursed when he heard from the returning horsemen, damn damn damn! Fifteen hundred of his men slain, or wounded. Half of his mounted force, including his best cavalry commander. Who would have thought Romans capable of such opportunism- sending legionaries without horse on a march to lure in unwary horsemen, then smack them with spear-wielding bowmen? Roman foresters! It was utterly dishonorable!

And costly, he winced. There was no avoiding it now. Inditrix had not only failed to blunt the legions, he had gotten himself seriously blunted instead. The only way he could prevent a link-up of this army with the two besieged legions inside Moguntiacum was to meet them in open battle with his entire army, and hope the fools in the stone castra do not realize they were alone.

********** *********** ************ **************

Julius Classicus felt a rush of relief when he saw the road disappear into the cleft of two wooded hills up ahead. There, he thought, there is where I stop the Romans. If I fail here, they move down river to where the terrain flattens and the forests thin out to where their cursed cohorts can deploy. We would be crushed there, but not here. Here we can win.

“Evrian, deploy your swordsmen in the center of the road,” he ordered, “up ahead where the treelines are narrowest. Sigmund, your warband goes to the east flank, and Gorn your to the west.”

“Among all these trees, our horses are useless, Julius,” Camdor the new cavalry chieftain pointed out. “So where do we deploy?”

Classicus pointed to the west, in the meadow on this side of the tree line. “Go there, with two thirds of your warhost. Pick a good chieftain to lead the others, and have them go to the west.”

Classicus looked back, and cursed his lack of foresters. The Romans had foresters, why couldn’t he? Yet he had slingers and javelineers- some of the finest. These he deployed in a skirmish line to the front of his forces.

“Porthicus, your warband will be placed in the center, behind Evrian. If the Romans threaten to break through anywhere, I want you to let them. Do you hear? Let them break through. And when they do, and spread out as is only natural when they breach the front, then and only then do you smash them.”

Porthicus smiled cruelly. “Aye, lord. If they break through, let them come and disperse, easier meat for our blades when we hammer them,” he repeated, to the nodding of his general.

Classicus looked to his last two warbands- Germani from across the Rhein, with a mix of weaponry and mix-matched armor among them. They were here to fight, yet would loath the orders he was about to give them. No matter. If they obeyed, they would be able to let flow far more blood than they shall shed.

“Jorg, Adelbart,” he said, addressing the two chieftains, “Your men will occupy the woods to either flank. Do not, repeat NOT, be seen. Our plan is simple- we fight, we fall back. The Romans will pursue, and then we hold them over here. That will bring the battle past your hidden warriors. Once the Romans are fully engaged, I shall blow the rams horn twice, then twice again. That is your signal to pounce. Drive them in on each other, and we shall win the day.”

He looked back at Camdor. “That is when you come into play, cousin. You thunder down upon any who flee, and slaughter them all. If the Romani deploy as usual, their chieftain will be outside the pocket. He is yours. Slay him, and the army falls apart.”

Camdor smiled. This was more like it. He wished Inditrix had lived to see this battle- Treveri warriors defeating an entire army of Romani. But he was dead, and now Camdor led the Treveri Horse.

********** *********** ************ **************

“The XXI Cavalry Auxilia reports Gauls up ahead, ready for battle, sir,” a horseman reported to his commander.

Cerealis had the scout draw in the dirt a map of the area and show where and how many. Satisfied he knew everything, he dismissed the horseman and sent for his legates.

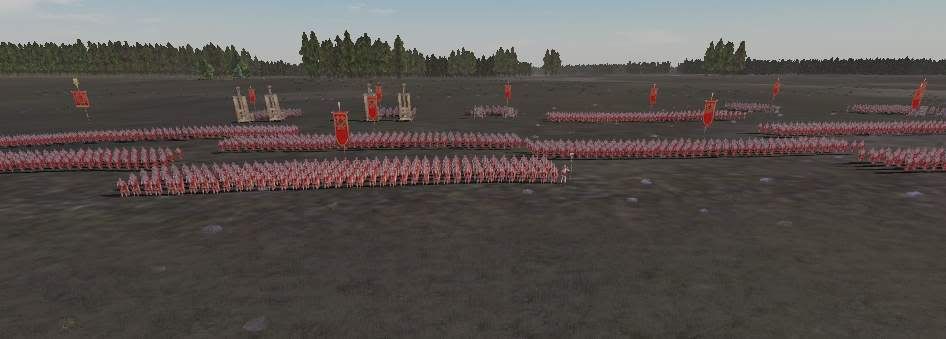

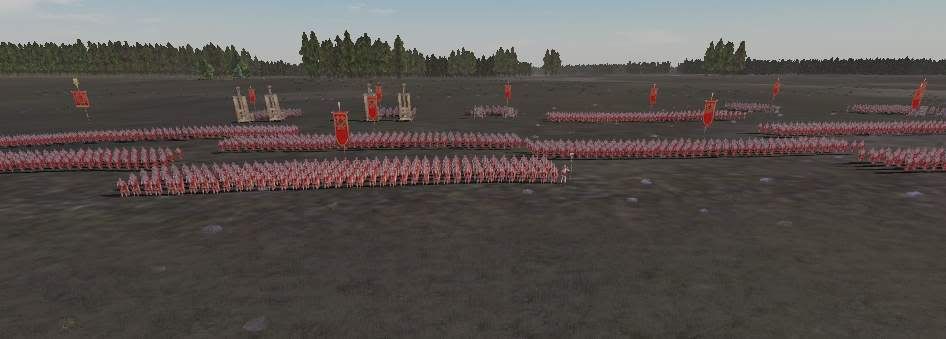

“It will be a battle,” he said joyfully. “We shall deploy our legions six cohorts abreast, four in the second line. I want the XIII Gemina on the left, the XXI Rapax in the center, and the II Adiutrix on the right. Messala, your XI Claudia will be behind the Rapax, as my reserve.”

“Why do the sea-mutts get the position of honor?” Messala wailed. “By rights that position belongs to the XI Claudia as senior legion!”

“Those sea-mutts kicked the crap out of the Treveri Horse the other day,” Cerealis replied, jutting forward his chin as if daring the legate to object to that simple fact. “The XXI took some casualties, so I am putting them in the center. And you, you young ape, are my reserve in case the sea-mutts get into trouble. Think of your reputation then- savoir of a legion.”

Messala was now satisfied, but Rutilius was fuming. But the difference between the two was apparent- Rutilius had the discipline to keep his mouth shut and temper hidden whereas Messala did not. Rutilius also knew that words were fine, but deeds counted. He will show them tomorrow what a sea-whelp legion could do.

********** *********** ************ **************

The two armies met in the morning, with the sun halfway to its zenith and no clouds to cover its glory. Sol Invictus could watch the coming battle unhindered.

The Treveri opened the battle with their skirmishers leaping forward and releasing their missiles. Slings carry a good ways, but javelins did not. Mixing the two together meant that the Romans were peppered with stones they could do little about. The threat of a sudden rush by the javelineers or the men behind them made forming the testudo a bad option. And the horsemen behind the lines of infantry made it suicidal. So they had to brazen out the barrage until they were within range of their own pila, and then payback was in order.

The II Adiutrix halted when the first stones fell. Rutilius said not a word, but marveled at the unity of his legionaries. No commands were issued at all- they just stopped, unslung their bows, strung them, then lifted and let loose.

The silence of the action drew no notice from the Gauls, who merely wondered why a third of the Romans suddenly stopped. Some thought it was in awe of their marksmanship, others cowardice. It wasn’t until angry wasps shot forth from the halted legion that they understood. And by then it was too late for many. Naval arrows had good penetration- those thinking to block the inbound arrows with wicker shields discovered this fact in a crude surprise.

The surviving skirmishers in front of the II Adiutrix had enough. They fell back to behind the thicker shields of wood and flesh of the main battle line. Rutilius had his lead cohorts fire two volleys into the skirmishers before the XXI Rapax before hastening to reform his line. The bows were left strung, cast down for the following cohorts to scoop up, as the lead cohorts rushed forward.

The skirmishers before the XIII Gemina got off a few more volleys before the Romans raised their pila. This was their clue, and they bolted from the field. Cursing, the legionaries of the XIII Gemina lowered their pila and resumed the march. Thirty paces later they raised again, and this time let fly, along with the pila from the XXI and the II Adiutrix.

The flight of pila landed hard among the Treveri and German infantry. The rushing legionaries followed closely behind, and a titanic crash of steel on steel resounded thoughout the valley. The battle was joined.

It seemed a walk-over. The Treveri and their Germanic allies fought well, but lost three men for every Roman they brought down. That damned brass-rimmed scutum was just too hard and too big for the long Gallic swords to break, and the darting gladii of the men behind that portable wall were bloody sharp and quick to stab into a gut here or a leg there. Neither Gorn nor Evrian thought their men could take much more of this.

Neither did Classicus. He blew his rams horn once, then once again. The Treveri fell back, screened by a barrage of javelins and axes.

“Yes!” cried Cerealis when he saw the Treveri retreat. “We’ve got them on the run. Legions, Advance!”

The legions surged forward to the call of the trumpet. The Treveri stood fast at a second sounding of the rams horn. The battle resumed.

“Sabinus!” Rutilius called. “Our front line is holding it own wonderfully. Take the four cohorts of the second line and march them in column around our flank. Clear the woods of hostiles, then fall upon those facing us from the rear.”

Titus Flavius Sabinus was overjoyed. His first command! He rushed off before his legate could change his mind and send the more experienced Arrius instead.

He grabbed the cohortal insignia of the right flank cohort and faced it toward the east. Calling out his orders, he led the cohort along the rear of the front line and into the woods beyond. Once past the last cohort, he looked to see if the other cohorts were following. Two of them were, the last was involved with providing archer fire to relieve a battered cohort of the XXI Rapax of some of its assailants. No matter, three were enough.

********** *********** ************ **************

“We are undone,” a German whispered to Adelbart. “Three cohorts come. They know.”

Adelbart looked through the woods and saw the Romans approaching. Though they did not look alarmed, he saw that they were in battle order and wary. He agreed- they knew he was here.

He has sat still long enough. His muscles ached to shear Roman heads from their necks, and arms from their torsos. He rose, and his men with him.

“Walhalla!” they roared, and fell upon the men of the X, IX, and VIII cohorts.

********** *********** ************ **************

“Oh cacat” is not an authorized command to give one’s troops, but the words coming from the tribune’s mouth were clear enough. The men of the II Adiutrix reacted as they had been trained these past months, their minds in shock at their first real confrontation but their bodies reacting instinctively to the battle drill. They closed ranks, locked shields, and bore the brunt of the francisca attack on their scuta. Then they threw their pila as taught, though the enemy was close enough to spit upon.

Regulations say at that distance one should draw swords, but that regulation had yet to be taught. And well enough, for the pila left their hands with desperate speed, and lost little of their power over the short flight. The front rank of Germans went down hard, tripping up the second rank. By the time those men recovered and joined the third rank in storming the Roman lines, the former marines had their gladii in hand and were ready.

It was a brutal battle, but one in which discipline and formation was the key to survival. Sabinus fought on the line for a while, too busy remembering his training in the parry and riposte to realize he had killed his first three men ever. It was block, chop, and stab, over and over, keeping an eye on the weapon of the warrior before him and using peripheral vision to keep track of the duels to either side. The rush of battle focused him with an intensity he never before had realized. It took a centurion bellowing in his ear to bring him out of his battle madness, reminding him he was not a legionary but an officer.

He reluctantly allowed the centurion to take his place. His duty was not fight and die like a soldier, but lead and direct as an officer should. That’s when he saw the VII cohort coming up to join the other three. He led them onto the flank of the Germans, feeling again that intense euphoria by joyfully ramming his gladius home time and again while smashing down the dying warriors with his scutum to get to the next. About him the men of the VII cohort did the same.

The threat evaporated. The German line disintegrated, and fled.

“That was easy,” he grinned to a centurion, who grinned back. “Now, on to the rear of those fellows plaguing our comrades!”

While Sabinus was clearing the east, the XIII Gemina was finding out the hard way that there were Germans to the west as well. A rams horn had sounded twice, then twice again. Germans spilled forth onto their flank, and into their rear. The legion buckled under the heavy assault, and threatened to collapse.

“Legio XI Claudia! Advance!” ordered Vipsanius Messala. His XI Claudia followed its eagle into battle to the west, catching the Germans between the rear cohorts of the XIII Gemina and itself. It was a slaughter. Jorg and his men died in place with steel in hand, as had Adelbart and his men. Now it was just the Treveri remaining.

Classicus saw the Eagle of the XI move, and the Romans pouring forth from the woods to the east. His ambush had failed, and he was about to be encircled like he had tried to do. There was only one thing to do.

“Camdor! Attack to the east, and screen our retreat. All others, disengage and retreat!”

Up and down the line the command went, and where it went, men turned to flee. Unencumbered by heavy armor, they soon outraced the pursuing Romans. They had lost many men in the failed ambush, three or four of ten, but by the valor of Camdor and the sacrifice of Sigmund, six or seven of ten managed to get way.

Classicus knew the war was over. It was a matter of time now. The Romans were not even blunted, and his army heavily damaged. He sent a runner to Joris besieging Moguntiacum, and another to Julius Sabinus near Lugdunum. It was time to consolidate if anything was to be salvaged.

********** *********** ************ **************

Decius Paullus was on the walls of Moguntiacum at dawn, again for the umpteenth time, watching the apes besieging him. His keen eyes were squinted for better vision and his ears were open and clean, yet for once he could discern no activity in the woodline sheltering his besiegers.

"Thos bastards have to be there," he muttered. "They've been there for two months now."

"Do you think they are finally finished preparing for their storm?" his primus pilus asked. Like his legate, he had spent his entire career on the border and knew better than to assume the stillness of the woods meant their besiegers had fled. "If so, expect them to attack with the coming of the sun tomorrow, as is their custom."

"I see movement, Gnaeus," the legate interrupted. "Ready the men. I think they are coming now."

Gnaeus Fulminus spun about and drew in a deep breath to bellow out the command. A gasp from his legate brought the unspoken command to a halt.

"Eagle!" exlaimed Paullus. "I see a silver eagle! They are here!" he cried in joy, "the legions are here!"

Fulminus let out his breath in a sigh of relief. "That's why the bastards besieging us disappeared- our army relieved us."

"Or it is a trick," Paullus suddenly spat seriously. "The gods know they have Eagles and armor enough to fake a legion after slaughtering Lupercus and his men. Let's be safe. Sound the alert, but ensure every man knows not to let fly a single missile without my express command. Just in case."

The primus pilus saluted. "Good idea, sir. I'll spread the word."

The legions were no Germans, nor were they Gauls clad in Roman armor. The lead legion came closer and its insignia was soon recognized by the men, who embraced each other in sheer relief. The XXI Rapax, taken by Vitellius to Rome, had returned to the Rheinland.

The gates opened to a howl of joy, and Decius Paullus sallied out with a small contingent of officers and centurions. He strode proudly forth to the Eagle, seeking the legate. Finding him, he reached out his hand.

"Decius Paullus," he announced. "Commander of the XXII Primigenia and IV Macedonica, commander of Moguntiacum and acting governor of Germania Superior."

The legate took his hand. "Lucius Amensius, commander of the XXI Rapax. Happy to see you are still around."

"Amensius?" asked Paullus. "We had atribunus militum of that name in the V Alaudae last year."

Amensius laughed. "You are not the only one promoted to legate, Paullus. That was me then, before our legate Fabius Fabullus got himself and half our legion killed at Bedriacum. The XXI Rapax lost a lot of officers in that battle, so some others and I transferred in to help bring her up to strength. I was made legate."

Paullus looked down at the mention of the man’s parent legion. "You know what happened to the rest of your legion here, do you not?"

Amensius frowned. "Aye, we heard. Arrius told us."

Paullus lit up at the mention of his former colleague. "Publius Arrius? Where is he now? He was a de facto legate here, before I sent him to hurry you up."

Amensius shrugged. It was a big army, and he was more concerned with his own legion than another. He suddenly looked up. This one tribune he did remember. "I think he is tribunus laticlavius in the outfit behind me- the sea-mutts. Good ones, though- they kicked the living crap out of a horde of Gallic horse a few days ago."

The conversation ended abruptly as the generalis approached. Cerealis looked over the two men, received their salutes, and frowned.

"You are Paullus?" he asked bluntly. Decius affirmed he was. "A tribunus?" Again affirmation. "And commander of two legions now?"

"And brevet governor of the province, sir," he added. "In lieu of anyone higher. All of our legates and generals are dead. Sir."

"Report, in your own words, and spare nothing," Quintus Cerealis ordered. "I have heard nothing but hearsay and second-hand reports since leaving Italia."

Paullus laid it out for him, succinctly and sparing no detail. Flaccus, the governor, had been murdered by the men of the I Germanica and the XVI Gallica. Then those selfsame slovenly fools abandoned a castra laden with supplies and weapons to the enemy. Herrennius Gallus was killed retaking the post. Later, the same men who killed the governor stood by while a deserter executed Caius Dillius Vocula. Both legions did more than surrender to the revolting Gauls- they went over to serve them. The V Alaudae and the XV Primigenia finally surrendered a depleted Vetera in exchange for safe passage, but were murdered in the woods anyway. Germania Inferior was now the Batavian Kingdom, and Germania Superior was reduced to the post of Moguntiacum and its immediate environs.

This was the third time Quintus Petilius Cerealis had heard the tale, and each time it was almost identical. Any last doubts, or hopes, that the stories were false or simply exaggerated dissipated. His respect for the men who lived through this catastrophe, and those who fought hell and high water to prevent it, rose even higher.

"I am going to rename your IV Macedonica, Paullus," he said. "From this moment, the IV Macedonica will be known as the Legio IV Flavia Felix, the lucky. Do you have a problem with that, legate?"

Paullus shot proudly to a sharper stance of attention when he heard his new rank. "No sir! No problem at all!"

"I won't rename the XXII Primigenia, out of respect for Caius Vocula, whose legion it was and tales of whose honor has reached the ears of Rome. Instead, those of the legion who had fought its way to Vetera and back shall receive a thousand sesterces reward each for their honorable campaigning."

"That will be the entire legion," Paullus acknowledged. "All forty-four centuries remaining of them. Any chance of the IV Flavia Felix getting a reward as well, sir?"

Cerealis turned feral at the comment. "Paullus, you lost two entire legions slaughtered like helpless sheep in the woods, another two legions deserted en masse to the enemy, and got two legions cooped up here in Moguntiacum. One Roman fleet has been captured intact by the enemy, and another beaten so bad that it is not fit for sailing north of Bonna. That's not counting the four legions of auxilia that that turd Vorenus lost to the Germans that started off this entire mess. The only thing keeping me from having you cashiered was that you and Vocula were not in command for most of it- you two inherited someone else’s mess. So don't press your luck."

"Yes sir, " Decius Paullus gulped. When the general laid it out so plainly, it was indeed a disaster beyond proportions, and his IV Macedonica- sorry, Flavia Felix- had done nothing more than garrison the provincial castra and build that battered second fleet. Meanwhile the XXII had fought at Novaesium, Gelduba, Vetera, Novaesium again, and then again here at Moguntiacum. They had earned a reward; his legion had not. "I apologize, sir."

Cerealis accepted the apology wordlessly. "I will move the XXI Rapax and XI Claudia into the castra. The II Adiutrix will most likely build its own camp over on that hill, while the XIII Gemina will camp outside your gates. In the meantime, son, take me to your praetorium and show me the ground between here and Batavodurum."

Paullus saluted and led the relieving army into the last Roman outpost in Germania.

********** *********** ************ **************

Gaius Julius Sabinus was overjoyed at his army. He was the Emperor of Gaul, elected so by his bloodright as descended from the Great Gaius Julius Caesar for whom he was named. His army counted thousands upon thousands of Gallic warriors who had risen up against the oppression Rome had laid upon them. Proof of his prowess as an emperor lay in the forefront of his army, where two formerly Roman legions now deployed against the Sequani. Those tribesmen at the foot of the Gallic Alps whose fertile valley and strategic position within the oxbow of the river should by rights be his, had refused to join the rest of Gaul in rising up against the Romans. For that, they shall pay and pay dearly.

Well, by nightfall, his Roman deserters will secure him those valleys and the loyalty of the survivors, as well as the prettiest of Sequani women with whom to celebrate the victory. After Vesontio falls tonight, it shall be on to Massilia, the crown jewel of Roman occupation.

The I Germanica and the XVI Gallica deployed online in the Roman manner. Flanking them were warbands of spearmen- Roman-trained auxilia who had deserted their Italian masters and now served a Gallic master. To their flanks were the magnificent horsemen of the Aedui and the Arvernii- two tribes who had been bitter enemies in the time of his great-grandfather but now served him as brothers. To the rear of the Gallic lines was nothing- Sabinus was a Gaul and proud of it. No Gaul had ever held a reserve in the Roman manner- warfare was an engulfing charge that swept all before it. With this, and with a solid Roman center, he would claim that which was his.

The sun climbed the sky slowly while the men waited. Before them, the pitifully few Sequani warriors were drawn up in an old-fashioned phalanx contesting the only suitable ford for leagues around. Those Sequani were dressed in their tribal colors, a bright red for the day of battle. Suitable, thought Sabinus. The coloring will match the blood spilling on it soon. At last the sun climbed over the mountains to illuminate Sabinus and his bodyguards. That was the time. He raised his sword so that it shown in the sunlight, and waved it so the men watching him could catch the reflections of sunlight.

The emperor’s army surged forward in a rush of warcries, beating their swords against their shields. Before them, the Sequani stood solidly, watching as the Romans closed ranks to fit into the ford and the flanking cavalry began swimming the river. The lighter troops, the Gallic auxilia, heaved their boats into the slight current and boarded. The Gallic wave was coming.

Halfway across the small river, things went awry in the worst possible manner. The tiny Sequani phalanx hadn’t moved, but from both woods flanking the ford stepped forth hunters carrying bows. And torches. They began emptying their quivers into the paddling men, sending boat after boat careening away as the men dropped their paddles to grab up shields. The boats collided, spilling men into the icy river, ceasing their struggles as the weight of their fine chainmail armor dragged them beneath the current.

Then the archers began firing flaming arrows into the swimming horsemen. These arrows, with their pitch-soaked straw tied to the head, killed fewer, but had a deadly effect nonetheless. Where an arrow missed, it sizzled harmlessly into the water and was gone. But where an arrow hit, it spattered its burning mass over the shield or man, dropping to the horse. Horses react very violently when set afire, and within seconds of the first volley landing, maddened horses were dumping their armored riders into the river and scurrying as best they could for the comfort of dry land that did not burn.

The Sequani, for their part, cared not whether the horse came to their side or went the other- as long as the rider of the horse did not come with it.

When the archers emerged, the Sequani phalanx lifted its spears and moved forward to the river’s edge. Here they lowered their spears and stood ready to repulse any turtle that crawled out of the river. The legates saw this, and realized they would soon be taking arrows from both flanks as well as spears in their face. The grand Gallic wave envisioned by Sabinus had failed. There was only one thing to do.

“Retreat!”

********** *********** ************ **************

It was a bitter pill, thought Sabinus as he watched what was left of his army fall back from the outnumbered Sequani. But one with an advantage. He had lost many, but still had a viable army. And the messengers from Classicus told him that army would be needed now that he too had tasted defeat.

He would move north. The Sequani were a sideshow anyway. There were no threats from the prize of Massilia, only glory to be had. Glory can be reaped anytime, but not with a Roman army loose to his north. A Roman army could destroy his fledgling empire to its brittle core. No, Massilia and the Sequani could wait. Cerealis could not.

With any luck, he would be able to swing in behind that mighty army. Then, using the tactic of his ally Civilis who drove a similar Roman army from Vetera, he could seize the base at Moguntiacum, stranding the Romans far from home with no supplies. His army, reinforced by that of Classicus, would be well and truly able to slaughter those starving roaches. Then, he gloated to himself, then both the Sequani and Massilia would be his.

********** *********** ************ **************

“Form up your men, legates!” Quintus Cerealis bellowed. “There is a war on, men, and its time we got into it!”

Cheering erupted from the men who heard him, making it hard for the legates and tribunes to pass their own orders. The cheering died down, and the men began forming up for the long march north.

“Aulus Pedius,” Cerealis continued once able, “your XIII Gemina will lead the way. I want the XXI Rapax and the II Adiutrix following you in that order. Gnaeus Vipsanius, your XI Claudia will bring up the rear. We are going to Lugdunum.”

“Lugdunum?” Vipsanius Messala said in shock. “The Batavi are north, sir. Lugdunum is to the south- a far march south at that.”

“Sabinus is near Lugdunum with a second army of Gauls,” Rutilius informed him. “Including two of our traitorous legions. Would you leave that kind of combat power in your rear when striking off to the northernmost borders of the Empire?”

Messala snarled, then backed off as he saw the ramifications. The sea-whelp legate was correct- two renegade legions supported by a Gallic army running around in the rear had to be taken care of, or this army would face the same fate as that of Germania Inferior. One had to have a stable base when operating on the frontier- his service on the Moesian border taught him that- and those renegades threatened that. So it was off to Lugdunum to return it to Roman hands and destroy the Gallic emperor.

Word had come of the Gallic revolt, and its primary victim. Titus Cassius, praetor of Lugdunum, had fallen afoul of the Gallic plotters and had his head handed to him- literally. Neither Rutilius nor Arrius were surprised. Cassius had the opportunity to strip Civilis of most of his best cavalry- the eight cohorts that had so punished the I Germanica at Bonna- simply by paying the Batavian auxilia the donative promised them by Vitellius. He balked, and insulted the Batavians to boot, and off went eight of Rome’s finest cavalry to serve the enemy. He probably did the same thing to the Gauls, inciting Sabinus to act. No Cassius ever could part with gold once it came into his possession. This time that unwillingness to pay cost him his head, Rome its provinces, and the world a war.

“He doesn’t like you very much,” Publius Arrius said to Rutilius, indicating Messala. The two were awaiting their turn in the line of march as the legions set off. “Is it something personal, or is he just an ass?”

Rutilius laughed. “A little of both. He became a legate after Bedriacum, where he led a beautiful flanking maneuver that cut Fabullus’s men to shreds. You should have seen it, Publius, from where I was. It really was magnificent. Of course, he could not have done that without my help.”

Arrius narrowed his eyes. “You were a Vitellian, like me, were you not?” he asked bitterly.

“I am a Roman,” Rutilius replied in a voice of steel. “I serve Rome, not any one man.”

Arrius thought that over, and nodded. “You’re right, Marcus. Nobody is a Vitellian or a Flavian anymore.”

Rutilius nodded back and continued, “Fabullus had ordered me to take several cohorts and drive off the Flavian scouts I had seen. The scouts were the vanguard of Primus’s army, led by Arrius Varus. A cousin of yours?”

“That whoreson?” Arrius replied indignantly. “I should hope not!”

“Anyway,” Rutilius chuckled, “he was having a great time slaughtering the fleeing Vitellian outposts when I arrived and kicked his teeth in. Did you ever notice that dent in his helmet? I put that there. Drove him from the field squealing like a stuck pig. Then that idiot Fabullus with his strung-out legions refused to halt and reform, and fired me in the process. He then ran into Primus whose legions were in battle array, fought well until he died, and then Vipsanius there led the Moesians around and hammered the leaderless Vitellians.

“So, had I not infuriated Fabullus by reminding him that his legions were strung out and Primus had an army nearby, he never would have ignored me to continue the chase and gotten in a position where Vipsanius could crush him.”

He looked over to his executive officer. “He knows I was there and on what side, so he doesn’t like me. That prejudices him a bit. Plus I won the favor of Mucianus, whom he had been wooing. Which prejudices him even more.” He chuckled loudly. “The rest of it is because he is an ass.”

********** *********** ************ **************

Frank of the Lion Terp Village was a happy man. His Frisian warband and their Chauci reinforcements were charged by the great Seval to occupy the civitas of the Ubii and prevent the Romans from using its harbor and other facilities. He had been here for seven months now, garrisoning a ghost town and enjoying himself immensely with the few widows that remained after the brutal crushing of Ubian power.

It was no more than they should have expected, thought Frank. The Ubii were Germans, who fled their homeland and were settled in Roman Germania. They were so grateful to the sandal-wearers that they even renamed their tribe to the Aggripensi- in honor of Agrippa- and their civitas to Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippensi- the Colony of Claudius with the Altar to Agrippa. They sided with the Romans against their brethren in this revolt, and for that they were punished harshly- destroyed as a powerful tribe and reduced to scattered clans.

Though here in Colonia the savage onslaught of the Batavians and other Germans against the Ubians was tempered- Colonia had sheltered the son of Civilis from Nero, and in gratitude, he ordered no pillaging or punishing of the city itself. Its hinterlands and other villages were ruthlessly expunged, but Colonia itself was sacrosanct. The depopulation of the countryside as the Ubii fled the onslaught led to their cousins of the city fleeing as well, leaving Frank and his five hundred Frisians little to worry about. And since Seval was driving the Romans out of the provinces and Gaul rising in revolt as well, Frank had little worries about them either. So he and his merry men ate their fill, drank more than their fill, and chased whatever womenfolk they could find to pass the time.

The dearth of people changed once the Ubii admitted defeat. Seval gracefully allowed their survivors to return. Smart move, thought Frank as he made his rounds through the town. An empty Colonia was of no use to him. A Colonia filled with tax-paying people, living happily under the Batavian King, was a worthy prize. And the Ubii did return, dribbling back in small groups, returning to the houses and farms they fled. Not many, though, as most were dead, but enough so that soon there were several thousand Ubii and other Germani breathing life into the city again.

A maiden ran by, shearing Frank away from his daydreams. At first he thought he imagined the girl, then imagined her naked, but when she emerged again from around the corner, he saw that she was indeed real and indeed nude. She giggled and ran off.

What in Hel’s realm is that? He wondered. Intrigued at the mystery of the maiden and aroused by her blatant nudity, he followed. The girls came upon another girl- also nude- and the two ran off into a house, laughing.

Frank was more than aroused. Naked maidens in the streets of his town? They are asking for it, he decided harshly, and was determined to give them what they were asking for. Duty and honor evaporated with his rising manhood. How dare they!

He approached the house, silent except for the giggles of the girls, and threw the door open.

The girls jumped at his entrance, and bolted up the stairs to the upper floors. Exactly where I want you, Frank thought cruelly as he made himself ready. His weapons belt came off, followed by the shirt beneath. He threw his boots into a corner, then began mounting the stairs. He was not sure what spooked him, but he stopped and retrieved his dagger, just in case the girls needed more of a lesson than a man in bed. He was now suitably armed to take on the two maidens, and pursued them up the stairs.

And died.

As soon as he entered the room where they giggled, he stopped. He was enthralled and fascinated at the view of not two but four beautiful nymphs writhing nude on a bed large enough for six. As his mind fought to reconcile this erotic behavior with prudish Germanic morals, it ceased working. A cudgel, wielded by a man hidden in the room behind him, crashed into his skull, broke it, and mashed the brains within. Frank dropped like a pole-axed steer.

The clubman and a colleague then rushed forward and carried Frank into the room where they had hidden, and bashed his head again for good measure. They threw his leaking corpse onto the pile of Frisian corpses already growing cold while the girls ran downstairs to pick up his clothes and weapons for the other pile.

“Now, girls, out again for another one,” the clubman whispered. “Remember, only show yourselves to single warriors, and ensure they come alone. A few more and we will have enough arms and armor to fight honorably.”

All across the city, similar acts were taking place. Some saw maidens walk by, turn, and wink at the Frisian warriors, who returned the winks and gawked. The distraction of the maidens allowed Ubian boys and young men to approach the warriors unawares, and slit their throats from behind. Others had problems with their wagons, and asked the Frisians or Chauci for help, When the rough warriors ordered by their king to be kind came and lifted the wagon, farmers stabbed them with pitchforks and clobbered them with clubs. In the taverna, poisoned mushrooms were served in the stew for the Frisians- when the garrison ate heartily of the hunter's stew, they gagged and convulsed- easy meat for the Ubii men who drank only water and ate only the vegetables.

Karel the Fearless noticed something going on, though he witnessed no direct incidents. Yet his skin crawled with awareness that something was going on. Something bad. Something to be prepared for. To satisfy his intuition, he called the warriors in the Lord’s Hall together and had them don their armor and ready their weapons. It would not matter. Karel had ninety warriors in the hall, and the Ubians had three hundred with Frisian arms and another four hundred with makeshift weapons. And plenty of entrances and windows to enter with. Karel died bravely with his men, but he did die.

Colonia was free, and the Ubii celebrated their first victory of the war by casting the garrison in the refuse pit. The banners and standards of Seval and the Batavians were torn down and draped over the men before being set alight, burning the rubbish and the Frisians together.

Then their own standards were hoisted, and those of Rome.

********** *********** ************ **************

Julius Classicus and his ragtag survivors abandoned the idea of blocking Cerealis’s march north once Colonia erupted in counter-revolt behind him. Instead he chose to swing south around through the deep forests and effect a link up with his master, Sabinus. That would put two great armies- the Gallic and the Batavian- on either side of the Roman nut, where they could crush it between them.

“Hail, Gaius Julius!” he called, once in his master’s camp. “It is good to see you, my brother!”

“Likewise, my cousin,” Sabinus replied, downgrading the kinship claimed by the Treveri to something more suiting his lesser lineage. Still, he resented the claim. “I had expected you to bring less men, based on the reports you sent concerning your ill-fated attempt to stop the Romans south of Moguntiacum. I am glad to see the messenger exaggerated those losses.”

“We have been joined by the Catalauni and the Remi warhosts,” Classicus announced. “They have more than made up for my tribesmen who have fallen to Roman swords.”

“We will need your vaunted Treveri cavalry, and that of the Remi,” Sabinus acknowledged. “I have heard that Catalauni spearmen are reputed to be every bit as good as Germani for holding a spearwall. Is this true?”

Classicus shrugged. “I have heard the same as you, my lord, but have yet to see these men in battle. The Ambiani foresters, however, have proven their worth already- their skills fed our army on the march here.”

Archers! Classicus brought him archers! Now his army was truly complete! “Good, my friend, you have done well. Apart, we were like our ancestors before mine. Together we are stronger than ever. The Romani have not a chance!”

“That is good, my liege,” Classicus said. He looked about the encampment and saw how slovenly the warriors here were as opposed to his own disciplined army. He turned bitter at the blatant luxury being shown the emperor and added, “Because Cerealis and his army are coming against you. They have already taken Trevorum, almost bloodlessly, and are heading here.”

“What?” Sabinus cried. “Is he not continuing north to fight Civilis?”

Classicus was not much of a general, but he was a far sight better than the man he swore to serve. One would think a descendant of Gaius Julius Caesar would have some inkling of waging war, but the sloth revealed that the large majority of those genes must have gone into what ran down his mother’s leg after the deed. “No, Gaius Julius. He is abandoning the Batavi for the moment to meet us in battle. We can cut him off from Rome. Civilis cannot, not with two good legions in Moguntiacum and another in Argentoratum. Thus he will dispose of us first before continuing north.”

“Then we shall meet him on the field of battle and destroy him,” Sabinus announced proudly.

Classicus had his doubts. “We shall certainly try, lord.”

********** *********** ************ **************

The Gauls marched north towards the Romans, who were coming south against them. The Remi scouts saw their opponents first, and within hours the Gallic army was drawn up for battle.

Six miles away across the plain, the Romans did the same. The II Adiutrix built its camp as normal, despite the mockery of the other legions, and all settled in for the night. The sky that evening was blood-red, a foreboding omen, letting all know there would be much blood shed the following morning. Many prayed fervently it would not be their own. In the camp of the II Adiutrix, no man prayed. They were too busy preparing for their first true action.

“If the Remi are with them, they will have archers,” Salvius was saying. “Archers are not so freaking deadly themselves, but they can cause you problems. Arrows hurt, but rarely kill. Not with that metal harness you men have and those wonderful neck-shields some genius added to our helmets eons ago. The scutum you carry can also take quite a few of them.”

“We know all this already,” Lucius Pallius said, interrupting the lesson. “We use the bow ourselves, remember?”

“Can you use the testudo?” Salvius retorted. The wondering looks and blank faces of the centurions answered his question for him. He looked over to the legate and frowned.

Rutilius shrugged. “Hadn’t gotten to it yet,” he replied lamely to the unspoken chastisement.

Salvius sighed. “Let us hope the enemy doesn’t target us tomorrow. And as soon as we can, we will learn how condense our centuries together and shield them inside the testudo.”

“Oh, that testudo!” Pallius exclaimed with a laugh. “I thought you meant some kind of artillery piece or weapon or something. Sure, we can form the turtle. We use it to wait out hostile barrages in preparation for boarding. No sweat.”

Salvius let out a sigh of relief. Not too many of these lads will find their way to the Elysian Fields tomorrow after all.

Rutilius stood. “Carry on, Publius,” he said to Salvius. “Publius Arrius and I are going to see the commander for the orders for tomorrow. Titus Flavius is in command until we return. And Uncle, make sure he knows to get inside the testudo, too.”

Rutilius and Arrius returned after midnight. The battle plans had changed several times during the command session, and not every time for the better. But the objections and snide remarks died when Quintus Cerealis put his foot down and made his decision. Tomorrow’s battle will be so, and any unit disobeying his orders would be decimated. The other legates were in shock, but Rutilius was beaming with pride. At last, a commander with balls enough to take on a legion. Vocula might be dead, but another just as worthy was emerging.

********** *********** ************ **************

Aulus Pedius Macro drew up his XIII Gemina to the right of the road, in quincunx formation. Each man in the rear two ranks were carrying four pila instead of the normal two, while the two foremost ranks carried hasta given by the sea-mutts. Pedius sighed as he saw how much ground existed between his flank and the woods, open ground cavalry could use to sweep behind his ranks. He dispatched a runner to move his flank cohort behind its neighbor, giving his legion at least some sense of depth.

To his left, the II Adiutrix had done the same. No man carried a pila, as these were given to the XIII Gemina. But the II Adiutrix needed no pila today. They had their naval bows, and the rearward centuries had their hasta if the Gallic horse came to call. This was going to be a holding contest, nothing more. And that meant spears and shieldwalls.

To the rear, the cohorts of the IV Flavia Felix were arrayed in a single line, ready to dispatch units to either flank or support the center. Quintus Petilius Cerealis positioned himself in their midst, where he could best see the battlefield and order his most junior legate to support the line with his cohorts.

Now began the waiting game.

Gauls were incredibly petulant and impatient warriors. Their way of battle, practiced for millennia, was to form a long line and sweep forward. Everything they had went into the initial rush, which was why the Romans with their deeper formations trounced them time and again. But to be fair, Gallic steel was rather poor, and its wielders often out of shape. If a battle was not over within ten minutes, their swords were too poor- bent or blunted- and the men too tired to continue. With Gauls, it was all or nothing. Which was why Petilius Cerealis waited.

Sabinus saw the pitifully few Romans standing before his reinforced army. He called Classicus over, and pointed to the Roman formation. “I see three legions. I thought they had four.”

“We hurt them some before going down,” Classicus replied. “Maybe that fourth legion is in Moguntiacum, recovering- or disbanded to fill the losses of those three.”

“Makes sense,” Sabinus said. “Why else would he come after us, then stand there, unless he sees our power and is afraid?” He pointed to the north flank. “Classicus, take your army that way. I want you to focus on smashing that in like the Batavi do, turning it in on itself. I will have my forces do the same on the south. Maybe we can recreate one of Civilis’s victories here.”

Classicus held his mouth shut and thought. The Batavian Crescent worked well at Bonna, where there was only one legion. It almost worked at Gelduba, but the arrival of the fourth legion disrupted those plans. If Cerealis had that fourth legion lurking about somewhere instead of recovering at Moguntiacum, the only thing Sabinus would recreate was the defeat at Gelduba. He said as much.

“Vapors and fairy tales,” Sabinus said haughtily. “Look at them there, pitifully few. Would you, if you were a Roman commander on hostile territory, stand alone with so few?”

Classicus looked over the Romans and had to agree. If he did have more forces, he would have them deployed there, where they were needed. Still, the lack of intelligence concerning that fourth legion nagged him.

Classicus returned to his troops and signaled Sabinus with his sword that he was ready. Sabinus acknowledged the flashing sword with his own, and had his trumpeters blare out the attack. At the signal, the Gauls started forward and the Romans spun about and departed.

“What is this about?” wondered Classicus as he watched the Romans retreat in good order.

In the middle of the plain below the low rise, Sabinus had no doubt what caused the Roman retreat. They saw his numbers, which were more than twice theirs, and fled rather than die. He signaled the charge, to get to the cowards before they could find safety.

“Belay that!” Classicus shouted. “We cannot see over that ridge. Only fools rush in where they know nothing!”

His army slowed to a canter, and Sabinus, seeing that, did the same. The Gallic warhost maintained its integrity and reached the ridgeline as a whole, defeating what they thought was the Roman plan to disjoint the opposition and cut it up piecemeal. Instead, the slight rise gave them a wonderful view of the Roman line taking up positions before a line of artillery, with a proper Roman camp behind.

Classicus smiled as he took in the view. The mystery of the missing legion was solved- they were hiding in that camp, in case their brethren failed. The artillery worried him somewhat, but moving men were hard to land a rock upon. He let his attack continue.

Sabinus, to his right, did the same. The legionaries of his army saw the onagers and ballistas, and shuddered. They knew how those machines worked, and that they would be ranged to cover the hilltop. As one, they quickened the pace to exit the kill zone as quickly as possible.

Sabinus noticed the legionaries moving faster and ordered the rest of his army to follow suit, just as stones began hurtling toward them. Any who thought to remain in the impact zone soon thought otherwise, or thought nothing at all after being smashed to pulp. The Gallic warhost charged.

And stopped dead in its tracks a minute later.

From the woods upon either flank of the ridgeline emerged Roman legions, ready for battle. The XI Claudia came from the north, the XXI Rapax from the south. Both legions closed on the Gallic armies, sealing them inside a Roman box with falling stones for a lid.

Sabinus saw the legions closing and realized there was no chance. Only he, being mounted and far to the rear of his warhost, had a chance. He seized it with both hands and sped off, back towards Lugdunum and safety. Following him was most of the Treveri cavalry led by Classicus- far enough outside the box to find a flank and escape. The rest of the army watched sullenly as their generals fled and the Romans closed in.

His men, pounded and surrounded, and now deserted by their emperor, felt their courage desert them as well. First the legionaries, then the Remi cavalry, and lastly the Treveri threw down their weapons and shields in surrender. The Catalauni spearmen held out until a lucky trio of stones plastered their ranks. Then the survivors hurled their spears to the ground and knelt in submission as well.

“It looks like we won’t be needing the testudo after all,” Publius Arrius commented as he watched the Gauls submit.

“No, we won’t,” Rutilius replied. “Do you see what I see, Publius?”

Arrius looked out over the kneeling army. He saw lots of prisoners and slaves, and Romans who would be crucified, but nothing else. He said so.

“Tsk, tsk, Publius,” Marcus Rutilius chastised. “I see cavalry and auxilia for this army, if Quintus Petilius is smart enough to take it.”

“I think he is,” Arrius said, pointing to where the general was approaching the II Adiutrix. “Why do you think he is coming here?”

“Because of us and who we are,” Rutilius replied. And he was right. Cerealis issued the II Adiutrix a painful set of orders, then moved off to address the Gallic warhost, now suitably unarmed and moved away from their weapons should any change their minds. Rutilius ordered Arrius and his other tribune, Titus Flavius Sabinus, to carry out the order.

Cerealis stood before the Gauls. “You men have risen against Rome. By rights, your persons are forfeit and you are mine to sell as slaves in the markets of Massilia, your women and children to the slavers of Italia, and your villages ours to plunder and pillage. This is the penalty for defying Rome!”

The Gauls knew this, having suffered this very punishment when the Divine Julius had come among them. But Quintus Cerealis had a surprise for them.

“You men had been oppressed by bad governors, and led by an incompetent fool to defy Rome,” he continued. “I promise to ensure Rome no longer sends greedy gold-diggers and sycophants to be your governors, erasing the cause of your revolt. I am willing to overlook this error in judgment of you following that fool Sabinus, and give you a single chance at redemption, if you so choose. Those of you who were soldiers in the auxilia must swear terrible oaths to both your gods and ours that you will return to the standards of Rome and serve out your terms with honor. Those of you who had not served Rome as soldiers, will now have the opportunity to do so. Those who refuse will find their way south to Massilia and over to Cappadocia, where you shall till the land and forget all about warfare. You have one hour to decide your fates.”

“Does that clemency extend to us, generalis?” called a centurion from the I Germanica.

Cerealis barked a terrifying laugh. “You cowards have committed the worst atrocity in Roman military history. You murdered two governors, including a general you all admired, and then deserted en masse to serve the enemy in wartime. Be lucky I do not have the lot of you flogged and beheaded this very afternoon!”

He galloped his steed away before he did order that punishment, and returned to the II Adiutrix.

“Are you ready, Marcus?” he asked the legate. Rutilius affirmed that he was. “Then carry on. I want the names of the men who murdered Vocula and Flaccus before the Gauls answer.”

“Aye, sir!” Rutilius acknowledged, and gestured to his centurions to begin their task as the general whirled about to return to his command group.

“Why us?” Arrius asked, once the general was away and the centurions off to interrogate the I Germanica and XVI Gallica. “And why our legion?”

Rutilius watched his centurions go with eyes narrowed. “It is obvious, Publius. We were in Germania for most of it, and our legion is former marines from the Ravenna fleet. They have no friends or grudges with those men, so they will be impartial. And we know the stories and tales of the legion, and can judge their veracity.”

The sun climbed into the sky, and a Treveri chieftain strode forth toward the Roman commander. “Lord, our hour is up. We have considered your clemency, very carefully, and wish to accept it. As we once served our emperor Sabinus faithfully, so would we serve the Roman emperor- faithfully, and with honor.”

“Not like he had much choice,” Arrius whispered with a sneer. Rutilius elbowed him for his levity.

“He had none at all,” the legate retorted. “But now Cerealis has his cavalry and auxilia, and sworn oaths to be loyal. Honor counts much among these men- they’ll keep their word. Now we have a very distasteful task to perform. Ready the men.”

Cerealis accepted the Treveri’s word of honor and made each man swear the oath of loyalty. Then he motioned to Lucius Amensius to begin processing the ex-prisoners into auxilia, while he himself went to where the II Adiutrix was holding the traitorous legions under guard. Rutilius handed him the scroll given him by the returned centurions, and the general moved to before the troops.

“The following men step forward,” he bellowed, reading out the eighteen names on the scroll. At each name, a man stepped forward, his head hanging low. When the names were read out, legionaries from the II Adiutrix came forward and collected the men, bringing them to the front of the legions.

“You men, some of you centurions, have offended Rome in the worst way. It was your mutinous actions and instigation that led to the deaths of two Roman governors, and the desertion of two legions. For this, I strip you of the honor of Roman citizenship. For serving the enemy against Rome while a state of war exists, you are found guilty and shall be punished according to the law.”

Nine wagons were brought forward, and the men stripped and bound face first to eighteen wheels. Eighteen men of the XI Claudia came forward wielding whips, and proceeded to lash the condemned. They kept it up until the skin was peeled from the traitors’ backs. Then and only then were the bleeding and crying prisoners cut loose from the wagon, forced to kneel facing their comrades, and beheaded.

Cerealis then nodded to the centurions of the II Adiutrix, who formed the prisoners up into ranks of ten. Then they passed along the ranks, issuing lots. When they returned, Rutilius held a bucket up while Cerealis groped inside. He pulled out a lot, and handed it to Lucius Pallis, the primus pilus.

“Number Four!”

At this announcement, the men holding the lot marked with IV marched forward and knelt. Each man removed his helmet. The others lined up behind him. Clubs were issued to the first man in each line, who then stepped forward while the drums beat out a slow tune. It was incredibly difficult, but at the blare of the trumpet, each man swung his club at the head of the kneeling man, felt the impact, and handed the club to the next man in line. The process was repeated until each man had clubbed the unlucky man who held lot number four.

The decimation was finished, but Cerealis was not yet done dispensing punishment.

“You men of the I Germanica,” he bellowed. “Your actions have cost you your citizenship, and your honor. You do not deserve to serve in the legions of Rome! You have sullied yourselves beyond redemption, in my eyes. Therefore I strip you of your Eagle, and disband you as a legion without honor.”

He gazed over the broken ranks, seeing their tears and hearing their sobs. He saw little of this during the decimation, which meant the sentence he pronounced was the cause. Good, he thought, perhaps they do have some honor.

“However, I am merciful, and you did shed no Roman blood during this battle. For that one redeeming note, I shall order you to march to Pannonia, to the VII Gemini and other legions in need of men, and allow you to serve out your terms of service in those legions, where maybe you will find the honor you lost in Germania. You will be branded, however, and any infraction- no matter how small- will result in your immediate crucifixion.”

He turned away from the legion and faced the second legion.

“You men of the XVI Gallica are also a disgrace to the legions. Gallica,” he snorted, “Conquerors of Gaul. Conquerors my ass! You have disgraced your legion and your history, and deserve neither! Therefore I disband you, and strip you of your eagle.”

The Aquilifer of the II Adiutrix moved forward and took the eagle from the stunned aquilifer of the XVI Gallica. He drew his pugio, and cut away the banner under the Eagle, then pared off the wreaths and awards of the unit as Cerealis continued.

“However, you men simply went along with your sister legion, and instigated nothing on your own. Due to that, I will show you clemency as well, though none of you deserve it. I hereby declare you to be the Legio XVI Flavia Firma- firm in faith to Flavius Vespasianus and his followers, for if you should break your oaths to him, you shall all find yourselves adorning crosses along the Via Mala. Is that understood?”

“Aye, sir!” rang the loud response from men who thought themselves dead in dishonor. The marine aquilifer gave the shorn eagle back to his colleague.

“You shall give a full cohort to each of the legions XI Claudia, XIII Gemina, and XXI Rapax. Further, you shall escort the disbanded legionaries of your sister unit to Pannonia. You are to ensure they are handed over in their entirety and none desert. What another general does with you is not my concern- my clemency ends here. Take your arms and your prisoners, and get out of my sight. I want you out of Gaul and Germania before the Kalends of Julius, fifteen days away. Any of you who remain in my provinces after that will suffer a slave’s fate. Now move!”

The men jumped, and moved. Cerealis turned away and headed for his command tent. The sight of the traitors he was forced to forgive sickened him. Oh, if only Rome was not bled so thoroughly dry by this terrible year! Those bastard were lucky- too lucky by far.

********** *********** ************ **************

"Seval!" cried a tired Batavian on a lathered horse. "Finally, my king, I have found you! A message for you from your cousin Prodigis in Britannia."

Seval- or Gaius Julius Civilis, as he was known to the Romans- looked up from the map he was studying. He was trying to track another cousin, that damned renegade Tiberius Claudius Labeo, who had suddenly become a very good guerilla warrior. He had him trapped somewhere in the lands of the Marsaci, but exactly where was painfully difficult to pin down.

"This had better be important," he said as he stood. Damn, he had lost his train of thought. Now he would have to start anew and rethink the entire problem of Labeo.

"It was important enough for your cousin to dispatch me from Eburacum, lord," the courier replied. "But as he sealed this message for your eyes only, I have no idea what he wrote."

Seval nodded and handed the exhausted man a horn of good Menapii beer. "Relax son, I am not so stupid as to kill the bearer for the news he carries."

Seval checked the seal- it was indeed from his cousin Gaius Julius Prodius, a commander of Batavian auxilia serving near the border with the Picti of the north. And it was still closed. He broke the seal, and read the contents. And laughed.

"That bastard Brinno will be getting into the war again, whether he likes it or not," he chuckled. "The Romans are making sure of that."

"What gives, lord?" asked a housecarl.

"The XIV Gemina from Britannia," the king answered. "It is moving to the docks at Londinium in preparation for transport. It seems they have received orders to invade the Cananefate lands and drive east to Batavodurum. They won't get far, not with Brinno guarding his lands like a father his daughter's virginity. Nice of the Romans to lose another legion to them- that will make five."

"We haven't heard from Sabinus in a while, lord," the housecarl reminded him. "And Frank in Colonia has been strangely silent."

"Your point?" the king asked with a cocked head.

"Lord, the Romans come from the west, and from the south. You are trusting mere Gauls to stop them, while you hunt Labeo here. Is it wise to trust Gauls to stop Romans? The whole of them could not stop Caesar and his four legions, and the Cerealis brings five from Italia, three from Hispana, and now one from Britannia."

"Cerealis is no Caesar," Seval replied. "And that will make all the difference. But you are right. We have wasted far too much time here chasing that ghost. Pass the word. We march back to Vetera on the morrow."

********** *********** ************ **************

Elsewhere, another rider was departing the Roman encampment at full gallop for a trip across Gaul. He was racing a clock- for he had to stop an invasion that was already embarking. How this came about was simple- Marcus Rutilius learned where Quntus Cerealis had ordered the XIV Gemina to land. And won the subsequent argument.

"You can't be so bloody stupid," the legate had railed at the general. "Or you were merely obtuse because of me?"

"It is not stupid to invade from the west while we tie up the Batavians here in the east," Cerealis roared back. "The XIV Gemina is a crack outfit, veterans all. They will destroy everything they come across."

"They said the same of the I Vorena," Rutilius reminded him. "And that legion went down harder than the II Vorena. They said the same of the V Alaudae and the XV Primigenia, and you remember their fates. And the same was said of-"

"Enough!" the general barked. He calmed himself before continuing. "I get your point, Marcus. But landing them on the island from the west is the best chance they have to drive to Batavodurum."

"Landing them on the Cananefate half of the island is the stupid part, sir," Rutilius said, his own calm returning. "The Cananefate destroyed four legions of auxilia who attacked them- veteran auxilia trained and equipped to fight as Roman legions. They then drove the V Alaudae and XV Primigenia away from Batavodurum, though they did not chase them back to Vetera as did the Batavians. Six legions these men have driven off, and now you send a single one to ravage their lands. You condemned that legion, sir, and destroyed any chance of having the Cananefate become again our Friends and Allies."

Cerealis ran the reports through his mind. The Cananefate were once Friends and Allies, and had been attacked by Vorenus seeking plunder, slaves, and wealth. They had destroyed Vorenus, but Vorenus was only to have a few auxilia. Where did the four legions come from? Had the greedy fool really managed to recruit so many Gauls and Britons? Yet Rutilius was in one of those unauthorized legions so they must have existed, and trained it while the legate and other tribunes drank unwatered wine and talked of their heritage. Those men are now dead, and Rutilius was now before him, a legate. And a damned good one.

"You are right," he said, making his decision. "I will dispatch a rider at once to change the orders. They shall land south of the Waal, and proceed east through the Marsaci, Menapii, and Tungrians, crossing north only after passing Cananafate land."

Rutilius had saluted, and the courier was dispatched post haste.

********** *********** ************ **************